It is not lost on me that I read a book about an apocalypse while living through the escalating contractions of an apocalypse. It is also not lost on me that I have gravitated towards dystopian fiction my entire life. It is a genre that strangely brings me comfort. Or maybe more accurately, it solidifies a sense of possible survival.

Future Home Of The Living God is a story expertly crafted by Louise Erdrich and it is the author herself we need to peer directly into in order to name why this book is so deeply felt. Louise is the daughter of a Chippewa mother and a German-American father. She is a poet and a storyteller, a woman who was raised between cultures and who shares the complexity of that throughout this story. The wide range of her writing explores both Christian and Native spirituality and this book - this brilliant and close-to-the-earth book - is no different.

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

- T.S. Eliot

Cedar Songmaker is the adopted daughter of white, upper-class, hippie lawyers in Minnesota. She was born Mary Potts, the daughter of Mary Potts, the granddaughter of Mary Potts - a long Ojibwe lineage - but was named Cedar by her Songmaker family. The question of how she was adopted outside of the reservation has never been answered and maybe Cedar hasn’t been too interested in those answers until now. We enter through the doorway of her life just as the world is beginning to dissolve. Evolution has reversed, winter has long disappeared, and animals, plants, and people are changing rapidly and without explanation. Babies are being born differently if they are born at all and people with uteruses are increasingly rounded up as ‘volunteers’ to carry what is left from IVF banks.

And Cedar, against all odds, is pregnant.

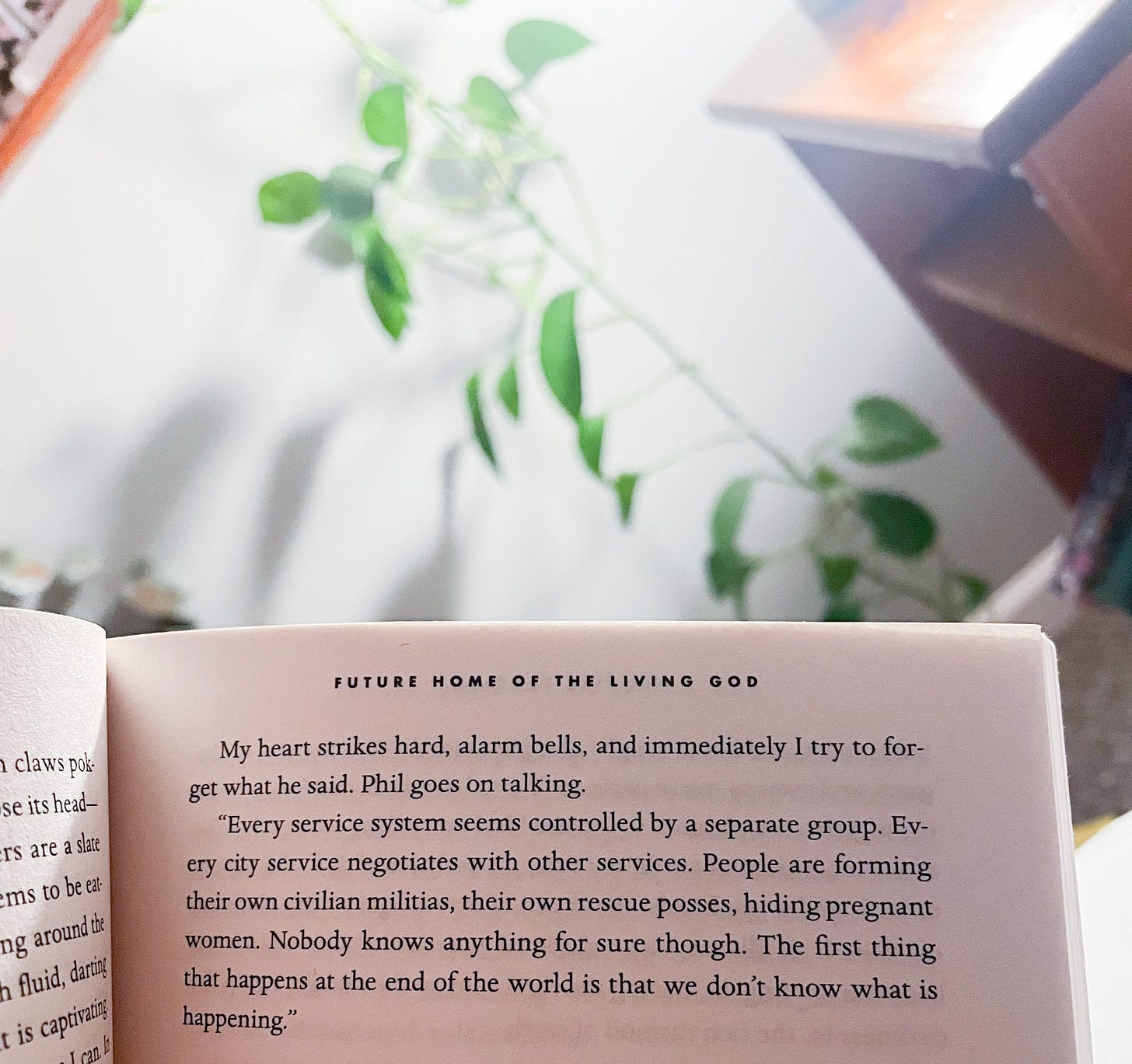

This book in its entirety is a diary written to the baby she carries, protects, and hides in her womb. It is a wide landscape of what one does as an apocalypse ramps up with a whimper, with a slow burn, with a slight but evident turning. It is a story that begins with Cedar driving onto the reservation to meet her birth family, wading into the wide waters of lineage and questions kept warm inside her body right alongside that unexpected fetus. She stockpiles food with a long shelf life, ammo, alcohol, and cigarettes to trade. She writes from behind closed curtains. She endures in hiding as long as she can. She discovers sisterhood in terrifying places, comes face to face with her own intuition, and experiences the tenacious grip of a mother’s bared teeth - both her adoptive mother’s and her own.

I read Cedar’s story in 24 hours. I read from the bathtub, from the glow of a lamp late into the night, curled into the couch while it rained. I read while our own real world grappled with genocide, with a wildly changing climate blowing an arctic chill across wide swaths of the country, tornados in Florida, and an avalanche in California on the wings of the word unprecedented. I read while Kate Cox had to travel out of Texas to have a life-saving abortion. I read while I did what I always do: tried to glean what warning, what wisdom this story had to pass down. Because we, beloved, are going to need it.

My friend

, an Indigenous Hawaiian artist and teacher, has said that what we are living now is only one of many apocalypses Indigenous people have endured. Maybe white people are more scared, she said, because this is just their first. I think about those words nearly every day. I think about 90% of Native Turtle Island people being killed off by settlers either by disease or by murder. I think about the ongoing terror of colonization in Palestine, Congo, and Sudan. I think about what the empire of whiteness has done to occupied people on their own land for a very very long time now. We will not experience, as my Christian upbringing once convinced me, a single end of the world. The world has ended many, many times now.Dystopian stories are not original material thought up by single authors. They are all, every single one, drawn from the already lived and ongoing experiences of oppressed and marginalized people. The forced use and even sterilization of bodies with uteruses is written into the collective trauma of Native and Black bodies here on Turtle Island. Nonconsensual sterilization of Native women was practiced into the 1970’s. This is so recent we should feel the chilling shudder of impact. Margaret Atwood has said that she drew from multiple historical atrocities to write The Handmaid’s Tale. There is nothing new under the sun, as even the lover king poet Solomon wrote.

We are living in a loop. Our history is bleeding into our present and overflowing into our future. It’s important we recognize this, name this, invite this into our storytelling. In all of our mythologies, there is a distinct message carried through time with such clarity: in order to end the monster you have to know its name. You have to speak it out loud. We are going to have to speak the dystopian monster’s name out loud and we are going to have to trust the people who have carried the knowledge of that name in their DNA, passed down through the survivors of multiple worlds that have ended at the hands of whiteness. We are going to have to be students of BIPOC storytellers in every genre. Written into the layers of that work are the important and intricate details about where we have been and where we are now. If we want to survive the end of the world we’re going to have to follow ancient wisdom that names the monster in the world and within ourselves. This will have to be both a community and a deeply personal act.

So yes, I read Future Home Of The Living God and it was a 5-star work of fiction, but it was more than that. Louside Erdrich wove a story that stands as a mirror. We’re here in the whimpering end of the world. What are we going to do with that?

*As always book links in this article are my own affiliate links with bookshop.org and lightly benefit both me and a small independent bookshop in Portland. I am wildly grateful when you choose to use my links so high five to those of you who do.

Oh my friend, thank you for sharing this story about what happened to the Aleutian people. I hadn’t heard it before and it feels so important to hold with reverence and grief. I’m grateful you laid it here on this community table.

This was the first book I’ve read from Louise Erdrich so it warms me to know you’ve enjoyed her other work (I’m adding a few to my TBR pile now). I hope it helps to hear that she does eventually answer the question about a white couple raising a native child, but I didn’t include the reasoning here because of spoilers. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts after reading so I hope you’ll come back here when you do.

I am writing from Western South Dakota, not far from the Pine Ridge Reservation where I once taught. Thanks for your wonderful review. There are only a few Louise Erdrich novels that I haven’t read, including this one. She also contributed at least in some degree to “The Broken Chord” attributed to her then husband, Michael Dorris. I have purchased most of her books and I’ve saved a few to savor sometime in the future…sort of like the stash of Halloween candy I often kept through November as a child. I have realized (and have happily forgiven Ms. Erdrich) that many of her books have unexplainable (or just unexplained) parts and pieces, so it will be easy for me to accept not ever knowing why a native child was being raised by a non-native couple…. I find her tales so beautifully enchanting.

On another note, two summers ago I was preparing to teach in Southwestern Alaska. While learning about the people who have lived on the Aleutian Islands and Alaska Peninsula for thousands of years, sadly, I learned about their brutal decimation by Russian fur traders—before Seward’s Folly replaced these Russian exploiters with American ones. I don’t remember the exact horrific number… but 90% (including deaths from smallpox, etc.) is very believable. One of the most recent tragedies involved removing all the inhabitants from at least two villages, along the westernmost edge of the island chain, after the Japanese invaded the Aleutians. The displaced Native people were mostly housed in an old vacant cannery on the mainland, and many died thanks to the terrible conditions. Incidentally, the survivors were never returned to their ancestral villages when the war ended. I felt, and still do, such deep sadness when I learned all of this. I’ve spoken with a couple of people who currently live or recently lived there (I didn't end up going) and find the glimpse of the life they generously shared with me inspiring and hopeful despite the unimaginable tragedy.